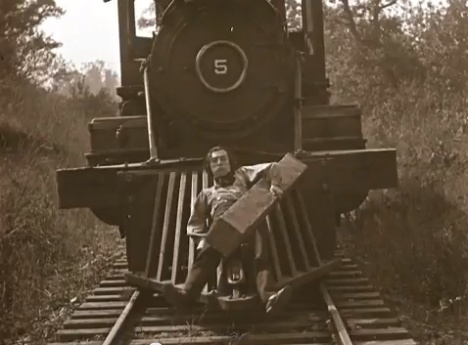

I might have been lying when I said I was lying. Actress Machiko Kyo takes in the horror of her situation — at least in her version of the story — in Kurosawa Akira’s landmark film Rashomon.

A man lies dead in a forest clearing, his wife has been assaulted, and a bandit has made off with their horse and possessions. This much is known, but everything else is called into question as the bandit, the wife, and the dead man (speaking through a medium) tell drastically different versions of how this came to be. And a story level beyond, three men discuss these testimonies as they take shelter from the pouring rain and, confronted with an apparent web of death and lies, ponder the nature of the human soul. Kurosawa Akira’s Rashomon (1950) was a major landmark in world cinema, breaking Japanese film into the global consciousness in a major way (and generally letting the West know that their was more than Europe and Hollywood out there). The film — which essentially tells the same story four times from radically different vantage points — is a remarkable deconstruction of narrative convention and calls into question the supposed impartiality of the camera’s gaze. Endlessly influential — the “Rashomon effect” has even entered standard legal parlance — the film calls into question the nature of truth and examines the urges and self-serving motives that obscure the pure core of our common humanity. (88 min.) Continue reading