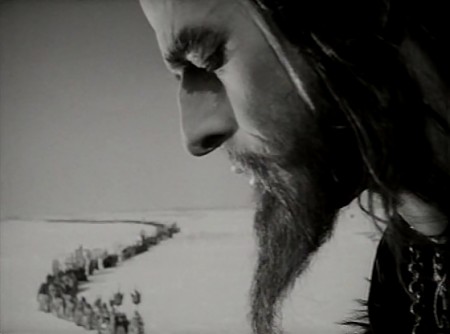

A house divided. A woman prepares medicine for her husband while trying to ignore the stares of her former lover in director Fei Mu’s tense domestic drama Spring in a Small Town.

We’ve been stuck here of late at FWAMY. So far we’ve yammered about 73 Sight & Sound list films, all of which come from just eight countries. So it is very nice to welcome a new nation to the fold: China. Spring in a Small Town (Xiǎochéng zhī chūn, 1948) was filmed in the short window between the end of World War II and the beginning of communist rule in China in 1949. As such it captures a very unique — if very brief — chapter of China’s history, and offers insight into what the country thought of itself before Chairman Mao. But the epic turbulence of this period is kept well to the background in Spring in a Small Town, which is a domestic melodrama that contains a grand total of five characters. An ailing man lives in the ruins of his family’s mansion with his wife, sister and a servant. One day the man is visited by a friend — a friend who used to be romantically attached to the sick man’s wife. It is a simple set up, but evocatively constructed to be a slow burn of passion versus duty; romance versus friendship. And while set in a society that lasted all of a few years, the beautifully shot Spring in a Small Town reaches for something universal and timeless. (98 min.) Continue reading