Why do you want to live? Powell & Pressburger pile on the visuals to create an extravaganza of music and dance in their final Sight & Sound film, The Red Shoes.

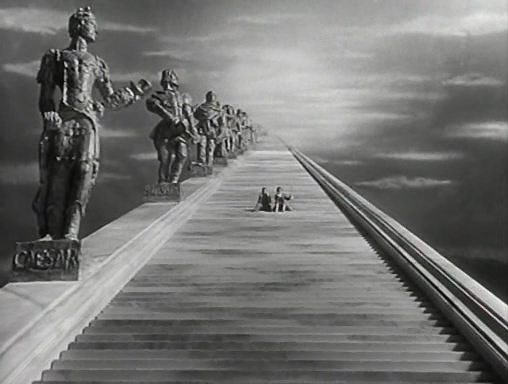

Ah, ’tis a sad day here in the land of Movie Yammers. Once upon a time (aka the beginning of 2014) S. and J. had a happy prospect ahead of them: six whole films by British filmmakers Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. Why, six films is almost an eternity of entertainment! And so we ventured forth through the dizzying days of Colonel Blimp to the Himalayan heights of Black Narcissus. But through it all we knew one day the Powell & Pressburger films (as well as our capacity for alliteration) would come to an end, and so they have with The Red Shoes (1948). And while we might no longer be dancing through Canterbury or Scotland — much less through the heavens themselves — The Red Shoes is a pretty grand way to end a run like no other on the Sight & Sound list. Loosely based on a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, the film recounts the story of three ambitious artists — a ballerina, a composer, and the director of a ballet troupe — as they struggle to balance love and art. Like the filmmakers’ Black Narcissus, plotting and character development are often a bit secondary in The Red Shoes, with the focus more on raw emotion and artistry than reason or sense. And through its kinetic ballet scenes and painterly blasts of Technicolor, The Red Shoes overwhelms with a torrent of visual splendor and daring quite unlike any other film. So, as David Bowie once insisted, “Let’s dance!” (135 min.) Continue reading